Source:

Brookings Institute, "Vital Statistics on Congress",

August 2014 edition

* HR Personal paid Staff of 18 full-time plus 4 part time or 19 x 435 = 8,265

If you divide the 708,056 citizens in

each 2010 Congressional District by 20 (one Representative and 19 Staffers),

the result is 35,403 citizens per one paid Congressional District public

servant, which is surprising close to 37,700 citizens per one HR Member in the

1790’s. The difference is, however, only one 2010 public servant in 20

serving 35,403 citizens is elected by the people in each

Congressional District.

Today, Congressional Districts now exceed a

population of 740,000 citizens and inexperienced staffers, usually not from

their Representative’s home district, are overwhelmed by the ever expanding

constituent base. According to the Washington

Times, these 24 year old staffers

are running the House of Representatives:

The most

powerful nation on Earth is run largely by 24-year-olds. High turnover

and lack of experience in congressional offices are leaving staffs increasingly

without policy and institutional knowledge, a Washington Times analysis of a

decade of House and Senate personnel records shows — leaving a vacuum that

usually is filled by lobbyists. Most Senate staffers have worked in the Capitol

for less than three years. For most, it is their first job ever. In House

offices, one-third of staffers are in their first year, while only 1 in 3 has

worked there for five years or more.

Among the

aides who work on powerful committees where the nation’s legislation takes

shape, resumes are a little longer: Half have four years of experience. When

Americans wonder why Congress can’t seem to get anything done, this could be a

clue. It’s also a sharp difference from the average government employee: Unlike

many state and federal workers with comfortable salaries, pensions and

seemingly endless tenures, those in the halls of power are more likely to be

inexperienced and overworked. Low pay for high-stress jobs with

less-than-stellar prospects for advancement takes a toll on institutional

memory and expertise.

While

senators make $174,000, staff assistants and legislative correspondents — by

far the most common positions in the Senate — have median pay of $30,000 and

$35,000, respectively, significantly less than Senate janitors and a fairly low

salary for college graduates in a city as expensive as Washington. Historical

pay records were transcribed from book form by the website egistorm.

The size of committee and members’ staffs have remained the same over the past decade, and salaries have often not risen with inflation — or at all. The average legislative counsel in the House made $56,000 last year, less than in 2007. While pay for parking-lot attendants in the House increased from $26,000 to $49,000 in the past decade, pay for staff assistants, who make up the bulk of the House’s workforce, rose from $26,000 to $30,000. That puts them in the bottom fifth of the region’s college-educated workforce. [3]

Moreover,

due to the large Congressional District sizes Representatives are obliged to spend

between six and seven hours a day calling and meeting with donors to fund their

next multi-million dollar re-election campaign. In 2013, the Huffington Post

published this DNC Congressional Campaign Committee slide that advises incoming Freshmen on a

Representative's Model Daily Schedule:

This

combination of an inexperienced staff working for elected House members that

spend 70% of their time fundraising has created a vacuum of competency, which

has been filled with seasoned experts paid by the money of lobbyists and other

special interests. National Public Radio reports that 11,000

Lobbyists are writing the House’s bills:

It's taken for granted that lobbyists influence legislation. But perhaps less obvious is that they often write the actual bills — even word for word. In an example a week and a half ago, the House passed a measure that would roll back a portion of the 2010 financial reforms known as Dodd-Frank. And reports from The New York Times and Mother Jones revealed that language in the final legislation was nearly identical to language suggested by lobbyists. It's been a long-accepted truth in Washington that lobbyists write the actual laws, but that raises two questions: Why does it happen so much, and is it a bad thing?[4]

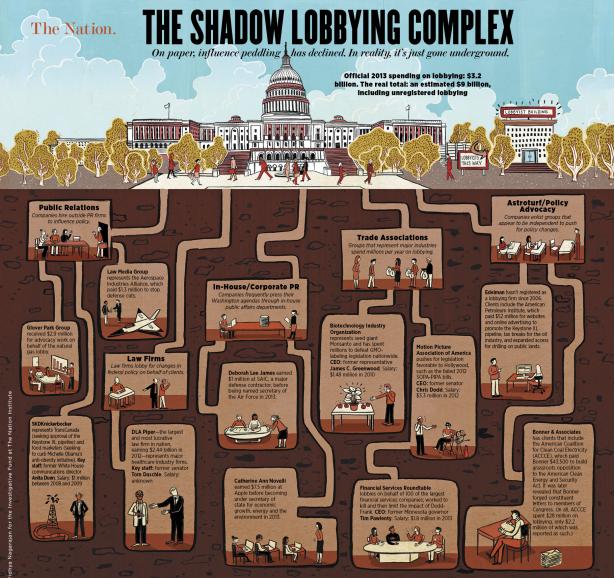

Lee Fang’s

"Where Have All the Lobbyists Gone?” not only provides a graphic

mapping out special interest influence on Capitol Hill but provides $3.2

billion annual estimate in lobbyist spending:

On paper,

the lobbying industry is quickly disappearing. In January, records indicated

that for the third straight year, overall spending on lobbying decreased.

Lobbyists themselves continue to deregister in droves. In 2013, the number of

registered lobbyists dipped to 12,281, the lowest number on file since 2002. But experts

say that lobbying isn’t dying; instead, it’s simply going underground. The

problem, says American University professor James Thurber, who has studied

congressional lobbying for more than thirty years, is that “most of what is

going on in Washington is not covered” by the lobbyist-registration system.

Thurber, who is currently advising the American Bar Association’s

lobbying-reform task force, adds that his research suggests the true number of

working lobbyists is closer to 100,000.

A

loophole-ridden law, poor enforcement, the development of increasingly

sophisticated strategies that enlist third-party validators and create

faux-grassroots campaigns, along with an Obama administration executive order

that gave many in the profession a disincentive to register—all of these forces

have combined to produce a near-total collapse of the system that was designed

to keep tabs on federal lobbying.

While the

official figure puts the annual spending on lobbying at $3.2 billion in 2013,

Thurber estimates that the industry brings in more than $9 billion a year.

Other experts have made similar estimates, but no one is sure how large the

industry has become. Lee Drutman, a lobbying expert at the Sunlight Foundation,

says that at least twice as much is spent on lobbying as is officially

reported. [5]

This

LAISSEZ-FAIRE citizenship that began with the people allowing “House

Apportionment” to stand at 435 Representatives has now extended into the

membership of the House itself. The Representatives have effectively

turned the power of the purse over to PACS, corporations, political parties and

other special interest groups. Every two years, these lobbyists fund

Congressional political campaigns with the millions of dollars needed to

persuade 540,000 eligible voters to elect and re-elect candidates to the House

of Representatives.

Moreover, Revelation’s quote: "So then because thou art

lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spue thee out of my mouth" has manifested itself as a Grand

Canyon size partisan divide in Congress. Simply put, large Congressional

Districts require large sums of campaign capital and the majority of members’

funding comes from lobbyists and their respective political parties. Such large

pecuniary donations are, by nature, "Hot & Cold" on specific legislative issues. There

is little money for the lukewarm compromising Representatives of the past.

Consequently, the House membership has evolved into a "Hot &

Cold" campaign capital divide.

The U.S. Constitution mandates that “All Bills

for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the

Senate may propose or concur with Amendments as on other Bills.” This sentence

was inserted into the U.S. Constitution to ensure that the power of the purse

be controlled by the legislative body most responsive to the people, the House

of Representatives. The blame for the National Debt, originates in the House of

Representatives, which is supposed to be the legislative branch of, for and

governed by the people.

Would a

6,151 member Article the First HR further empower the two-party system,

lobbyists and increase the federal bureaucracy to unmanageable levels?

If you view the House of Representatives as a team

of 435 Representatives and 12,000 federally paid staffers working with 11,000

lobbyists, one can readily deduce that the House already operates with over

23,435 people conducting its legislative business. Earlier, it was noted that

if you divide the 710,000 Citizens in each 2010 Congressional District by 20

(one Representative and 19 Staffers), the result is 35,500 Citizens per one

paid Congressional District public servant. We also noted that this “Public

servant” representation is surprising close to the 37,700 number of citizens

that each HR member represented in the 1790’s with no staff.

Unfortunately,

only 435 people or 5% in this Member/Staff HR team are elected and answerable

to the 710,000 constituents. What we have not addressed are the

11,000 lobbyist that have become an integral part of the 23,435

person HR legislative team.

Lobbyists are neutered

In an A1HR, these 11,000 lobbyists would

effectively be replaced by 5,716 Representatives (6,151 HR members - the

current 435 HR members). Thus the HR legislative team would be reduced

from a private/public sector employee mix of 23,435 to 18,151 public servants

of which 33% would be elected U.S. Representatives under an A1 Congress.

- In A1 Congressional Districts, a candidate would only have to reach its 38,000 eligible voters (The US Census places the voting-age population at 76% of the total population).

- Consequently, any citizen over the age of 25 could become a viable grass roots candidate for Congress, much like a mayoral candidate in a small town.

- Citizens would not need multi-million dollar media and other marketing expenditures to wage competitive campaigns to reach the 13,000-21,000 voters.

- The need for lobbyist campaign capital would be eliminated.

The National Media’s impact on HR races is

negligible

In an A1HR, the press would lose its impact on the

House of Representatives because free media and its endorsements, currently

needed to reach 740,000 citizens, would no longer be essential political

campaign components in Congressional Districts capped at 50,000 citizens.

The two-party political stranglehold is broken

In an A1HR would no longer rely on the powerful two-party political system to wage their grass roots campaigns. Independent and political parties could, once again, break the 5% HR membership threshold that birthed and expanded numerous political parties, including the DNC and RNC, in the 18th and 19th Century Congresses.

Gerrymandering

is invalidated

An A1HR,

would virtually eliminate state

legislature gerrymandering. U.S. Congressional District Gerrymandering has been practiced since

the Federalist and Republican Parties redistricting after the 1790 Unites

States Census. Congressional

partisan gerrymandering is commonly used to increase the power of a political

party but often two major political parties will collude to protect their

respective incumbents by engaging in bipartisan gerrymandering.

In the 19th Century jurisdictions began to engage in racial gerrymandering to weaken the

political power of minority voters, while others engaged in gerrymandering to

strengthen the power of minority voters. By the 20th century, the courts were

forced to grapple with the legality of these types of gerrymandering and have

since devised standards for the different types of gerrymandering.

Additionally, various legal and political remedies have emerged to prevent

gerrymandering, including court-ordered redistricting plans, redistricting

commissions, and alternative voting systems that do not depend on drawing

boundaries for single-member electoral districts.

|

Originally published on March 26, 1812 in the

Boston Gazette, this Elkanah Tisdale caricature satirizes the bizarre shape of

a state senatorial district as a dragon-like "monster." The new

district was created by Massachusetts legislature to favor the Republican Party

candidates of Governor Elbridge Gerry over the Federalists. The Federalist

newspaper editors, however, likened the district’s shape to a salamander, and

replaced “sala” with Governor Gerry's last name, coining the now familiar

political term, Gerrymander. - Image from the Library of Congress

|

The standards for congressional

districts are now quite strict, with equal population required "as nearly as is

practicable." In

practice, this means that states must make a good-faith effort to construct

districts with the exact number of people in each district within the state.

Any district with more or fewer people than the "ideal population"

must be specifically justified by a consistent state policy. And even

consistent legislative policies that cause a one percent spread from largest to

smallest district would likely be ruled unconstitutional.

The other major federal redistricting rule concerns

race and ethnicity. In the past, redistricting has been manipulated to dilute

racial and ethnic minorities' votes at the polls. The most familiar ploy is

called "cracking,” which is the splintering of minority populations into

small pieces across several districts, so that a big group ends up with a very

little chance to impact any single election. Another tactic is called

"packing," which is pushing as many minority voters as possible into

a few super-concentrated districts, and draining the population's voting power

from anywhere else.

The federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 was designed to combat Gerrymandering

cracking, packing and other techniques utilized to deny citizens the right to

an effective vote. This federal law provided the courts with new

powers to override inconsistent state laws that violated the Voting Rights Act.

It is agreed to by scholars that the geographic integrity of these ever-growing

congressional districts has worsened in the United States since the 1960's but there

is much debate over the reasons why. What the experts do agree on, however, is

maintaining geographic compactness of districts has long been embraced as a

traditional redistricting principle (see the "A Two Hundred-Year

Statistical History of the Gerrymander" by Stephen Ansolabehere & Maxwell

Palmer, May 16, 2015).

A1 Congressional Districts capped at 50,000 citizens would be

geographically compact. These small districts would eliminate the practice of

cracking, packing and other gerrymandering techniques because the populations

will be too small for politicians to splinter or pack groups without violating

the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

An Article the First HR virtually solves the challenge of

Gerrymandering.

The Wyoming

vs California Electoral College imbalance is rectified

If the House of

Representatives was not apportioned to 435 members and Congress followed

an Article the First apportionment like its 1790-1840

Congressional predecessors, the Electoral College Vote would adhere more

closely to the popular vote making Presidential elections more competitive.

The current movement to enact a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College in favor of a popular vote has virtually no chance for passage in Congress, let alone ratification by 4/5ths of the States' legislatures. Like the establishment of the equal State representation in the U.S. Senate, the Electoral College was a Small States/Large States constitutional compromise agreed to during the 1787 Philadelphia Convention. It was the Electoral College and other Small States/Large States compromises that eventually won the eleven State ratification of the current U.S. Constitution in 1788, which replaced the failed One State/One Vote unicameral federal government established under the Articles of Confederation on March 1, 1781.

The enactment of an Article

the First Apportion Law capping Congressional Districts at 50,000

citizens, however, would not require a constitutional amendment and

an Article the First Electoral College vote would more closely

resemble the popular Presidential vote, for example:

If

we take Wyoming, the least populist state, with its population of 1 564,460 and divide it by the

50,000 Article the First (A1) Citizen Cap, the math yields 11

congressional districts plus one electoral vote for each Senator or 13 total

electoral votes in a Presidential election. Now, the dividing of Wyoming's 564,460

citizens by its 13 Electors results in one electoral vote per 43,420 citizens.

Utilizing

the same A1 50,000 Citizen Cap formula for

California, the most populous state, the math is 38.8 million citizens divided

by 50,000 Citizens = 760 Congressional Districts plus two

Senators or 762 Electoral Votes. You then divide the 38.8 million population

by/762, the math yields 50,918 California citizens per one Electoral College

vote. The difference between the Electoral College vote and popular vote is

only 7,498 citizens.

Under the current 435 House member capped

Congressional District System, California has 53 Congressional Districts plus

two Senators or 55 Electoral Votes. California's 38.8 million citizens are thus

divided by 55 yielding 705,454 California citizens per electoral

vote. Now, if you take Wyoming’s one congressional district and add two

for its U.S. Senators this yields three Electoral Votes. Wyoming's 564,460

citizens are thus divided by three yielding 188,153 Wyoming Citizens per one

electoral vote. So the 705,454 Citizens equaling one vote in California minus

the 188,153 Citizens equal one Electoral College results in a 517,301 citizen

disparity per Electoral College Vote between the two States.

An A1 50,000 Citizen

Cap, however, corrects

this 517,301 person disparity yielding 43,420 Citizens per one Electoral

College vote in Wyoming versus 50,000 citizens per one Electoral

College vote in California.

This more equitable Electoral

College system is what the Bill of Rights framers

envisioned for all Presidential elections with its passage of Article

the First in 1789 and the huge Wyoming vs California Electoral College imbalance is rectified.

Is a

constitutional amendment required to create an A1HR?

No, the current cap on the House membership is a Public

Law, which can be changed without a constitutional amendment. Right now, with a

simple majority vote, Congress could repeal the current House Apportionment

Bill and cap Congressional Districts at 50,000 citizens as proposed by Article the First in the 1789 Bill of Rights.

What can I do to create an

A1HR?

The members of this 1789 Congress included two

future U.S. Presidents, three former Presidents of Congress, nine Declaration

of Independence signers, four Articles of Confederation signers, and 15 U.S.

Constitution Signers. Moreover President George Washington, Chief Justice John

Jay, Secretary of State and Declaration of Independence author Thomas

Jefferson, Secretary of the Treasury and U.S. Constitution signer Alexander

Hamilton, Attorney General and U.S. Constitution framer Edmund Randolph, and

Secretary of War Henry Knox worked behind the scenes to constitutionally cap

Congressional Districts at the maximum of 60,000 or 50,000 citizens. Their

debates and letters clearly indicate that the framers of the Bill of Rights wanted the House of Representatives to

remain answerable to people through the mechanism of small districts devoid of

any undue influence by special interests.

A1HR.org advocates the

enactment of a Public Law that caps Congressional Districts at 50,000 persons,

as proposed by the original first amendment in the Bill of Rights known

as Article the First.

This law would exponentially

reduce the cost of House of Representatives campaigns thereby negating special

interest campaign capital’s influence on HR legislation. The law would also invalidate the practice of

Gerrymandering, rectify the current Electoral College imbalance and eradicate

the need for political party partisanship in the House of Representatives.

In short, a Congressional

District cap of 50,000 persons will restore the collective wisdom of citizen

governance over the House of Representatives.

United States Census Bureau, Reports

and statistics from the 1890 census, Males of Voting Age table, page clxxviii.

Chart is taken from a 1993

Congressional Report and shows the increase in the number of staff for each

member of the House of Representatives since 1893. Before 1893 the House

members paid for their own staff. Since the 1919 staff allotment of two,

the House of Representatives has been fixed at 435 Representatives. For

more information on House staff and salaries please read The Number of

Congressional Staff Is the Real Problem by Daniel J. Mitchell

Luke Rosiak, Congressional

staffers, public shortchanged by high turnover, low pay, The Washington

Times - Wednesday, June 6, 2012

Alisa Chang, When Lobbyists Literally

Write The Bill, National Public Radio, November 11, 2013

Lee Fang, "Where Have All the

Lobbyists Gone? On paper, the influence-peddling business is drying up. But

lobbying money is flooding into Washington, DC, like never before. What’s going

on?" The Nation, March 10-17, 2014.

No comments:

Post a Comment